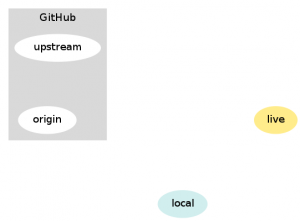

Often I find absolutely competent programmers, who aren’t involved in open source, either because they don’t know how to approach a project, or because they just aren’t sure how the process even works. In this article we’ll look at one example, the conference feedback site joind.in, and how you can use GitHub to start contributing code to this project. Since so many projects are hosted on github, this will help you get started with other projects, too.

The tl;dr Version for the Impatient

- Fork the main repo so you have your own github repo for the project

- Clone your repo onto your development machine

- Create a branch

- Make changes, commit them

- Push your new branch to your github repository

- Open a pull request

This article goes through this process in more detail, so you will be able to work with git and github projects as you please.

Continue reading